Malaysia is 48 on 31 August.

48 years after Independence (Merdeka), Malaysians still wrestle with issues of race, language, and religion. 48 years after the British exited, we are nowhere nearer to achieving a sense of nationhood, at least to this blogger. The post-Merdeka generation - like myself - knows no other land but this one, yet so many stutter at the mention of ‘patriotism.’ We still contend over history, unsure over the arguments that have defined our national psyche, wondering if it has not been hijacked to justify politics that divide and rule.

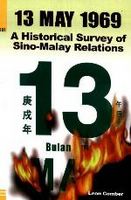

A friend loaned me this interesting

book by Leon Comber (who, as it turns out, is renowned author

Han Suyin’s former second husband), detailing the historical milieu that ignited the bloody fissure Malaysians know as May 13. It was a revelation to read that way back in 1927, racial sentiments were sufficiently pronounced for the British colonialists to acknowledge it (in opposition to immigrant non-natives, mainly Chinese and Indians) if they did not want to betray the trust of indigenous Malays.

Sir Hugh Clifford, High Commissioner of the Federated Malay States wrote regarding the ‘special position’ of the Malays:

“No mandate has ever been extended to us by Rajas, Chiefs, or people to vary the system of government which has existed in these territories from time immemorial…The adoption of any kind of government by majority would forthwith entail the complete submersion of the indigenous population, who would find themselves hopelessly outnumbered by the folk of other races; and this would produce a situation which would amount to a betrayal of trust which the Malays of these States from the highest to the lowest, have been taught to repose in his Majesty’s Government.”

W.G.A Ormsby Gore, Parliamentary Under-Secretary for the Colonies stated in a 1928 report that,

“Our position in every state rests on solemn treaty obligations…[the States] were, are and must remain “Malay” States and the primary object of our share in the administration of these countries must always be the progress of the indigenous Malay inhabitants….To me the maintenance of the position, authority and prestige of the Malay rulers is a cardinal point of policy.”

The ramifications of the above are obviously immense, hinting at a social contract that continues to this day to subordinate generations of non-Malays born and bred in this land to second-class citizenship. Worse of all, it has become enshrined as a taboo ‘sensitive issue’ - so our politicians tell us repeatedly - which we are not to question. Ever.

Dr Azly Rahman dares to ask in an article in

Malaysiakini if nationhood can be built around unquestioned historical precedents. He quotes Hannah Arendt, that history does not necessarily mean progress. In his blunt but insightful piece, Dr Azly suggests that to make history, we must be allowed to question it.

In this Malaysia in the year 2005, how must we construct a more accurate definition of a native, an immigrant, a first/second/third generation of this or that?

Why must we not question history if we are to become new makers of it? Why must we still treat the grandchildren of immigrants as ‘second-class’ citizens? Why must we not accord them with opportunities that resemble equitable/regulative justice? Have not their parents laboured for the prosperity of this nation, a nation that has trumpeted itself the world over as a modern developing state? Have not the children of these serfs and labourers think, act, and feel Malaysian enough to be treated as equals?

Why must we not declare, as the principles of social redistributive justice requires, that we must design a new social contract that will abolish all interpretations of human beings based on racial origin and use the abundant resources we have for the benefit of all - all the children and grandchildren of tine miners, rubber tappers, and padi planters, fishermen who were cleverly divided, conquered, and exploited by the British imperialists? [More]

Whatever our misgivings, we're in it together, and we'll have to make things work. There are positive signs that rumblings of discontent from the Malay intelligentsia and academics (like Dr Azly), NGOs, and others, are raising the bar for public discourse. For the first time, technology,alternative media, and online channels such as blogs, are involving Citizens Ahmad, Lim, Muthu, and Joe in the conversation. My hope and prayer is that it will swell into a force for good. Malaysia deserves more.

Some links:

WikipediaLim Kit Siang for MalaysiaBrandnewmalaysian: Conversations on MerdekaVirtualMalaysia's Tribute to Malaysia's 48th National DayFor Malaysia, a day for speaking out

Dad was a hoarder, possibly bordering on an obsessive-compulsive complex. And I am not just referring to books, papers, and magazines. He put away broken tools, containers, strings, nuts and bolts. Like the handyman he was always using throwaway materials to fix faucets and electrical appliances.

Dad was a hoarder, possibly bordering on an obsessive-compulsive complex. And I am not just referring to books, papers, and magazines. He put away broken tools, containers, strings, nuts and bolts. Like the handyman he was always using throwaway materials to fix faucets and electrical appliances.